As expected, and as priced in by financial markets, the Bank of Japan (BOJ) hiked overnight rates by 25 basis points (bps) on 24 January. The hike took the Mutan call rate to 50 bps, its highest since 2008; it was also the third hike since the central bank began tightening policy in 2024 and marked its most significant series of rate increases in the post-Global Financial Crisis era. The latest decision was not unanimous, as policy board member Toyoaki Nakamura dissented, favouring a hike only after confirming a rise in firms' earning power. However, at the post-policy meeting press conference, BOJ Governor Kazuo Ueda indicated that the majority of the policy board determined that given recent economic developments, including but not limited to an acceleration in December's core CPI to 3%, the economy is broadly performing in line with the BOJ's economic and price outlook. This performance by the economy and prices meets the conditions set out in past meetings to deliver additional, albeit gradual, rate normalisation.

Rates remain accommodative and real wages are back in positive territory

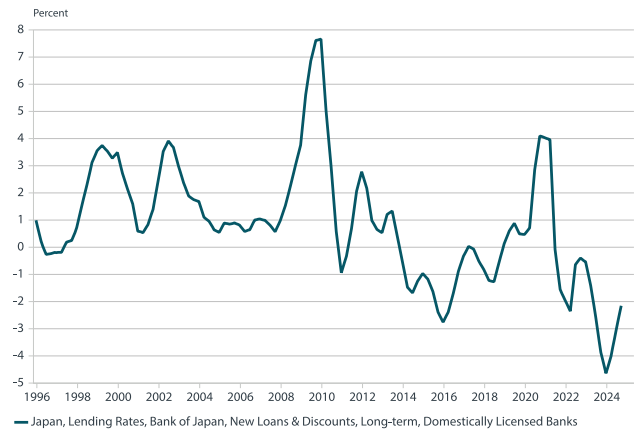

One message that Ueda delivered at the press conference was that interest rates remain accommodative, and at 50 bps, overnight rates have not yet reached a “neutral” level. When asked about neutral interest rates, Ueda merely pointed to history, which shows that in nominal terms, neutral rates have tended to fluctuate between 1% and 2.5%. Meanwhile, the market appears to have mostly priced in another 25 bps hike to 75 bps within 2025. Although neutral rates in any economy tend to be a moving target, we illustrate below that real rates not only remain negative, but they remain significantly below Japan's real GDP growth rate. Chart 1 plots the key “r-g” metric as of Q3 2024. It can be observed that an additional 25 bps keeps this metric firmly in negative territory, even though it moves higher than before the adjustment.

Chart 1: Japan's real interest rates are still accommodative

Source: Nikko Asset Management, BOJ, CAO

*Japan real interest rates - real GDP growth

Source: Nikko AM, BOJ, CAO

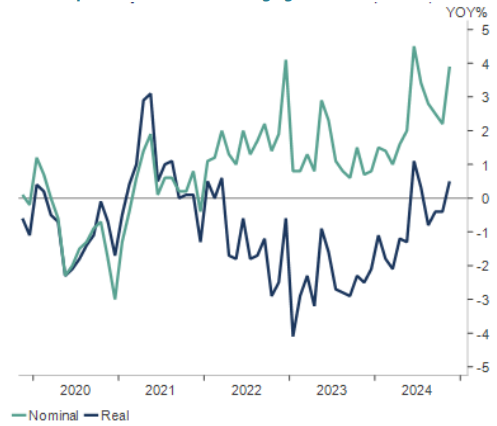

One factor strongly supporting the BOJ's decision to hike rates this month was the rise in real wages back into positive territory (see Chart 2), coupled with signals that the Shunto round of spring wage negotiations will bring another year of solid nominal wage rises, thereby contributing to a further elevation in real wages, inflation permitting.

Chart 2: Japan's nominal vs. real wage growth

Source: Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare

Risks ahead: “neutral” is now 25 bps closer

One thing that is certain is that overnight rates are now 25 bps closer to the “neutral” level. As each rate hike brings us closer to neutral—whether “neutral” monetary policy is achieved this year or the next—the BOJ will have to soon consider declaring victory against deflation. In Ueda's statement to the press, he portrayed the BOJ as being closer to this point than the government based on its view that the probability of a slide back into deflation (while not zero) is “very low”, at least in terms of achieving the BOJ's long-term price stability target of 2% inflation. The risks associated with designating rates as “neutral” are two-sided. First, calling an end to normalisation presumes that any further hikes after this point will be perceived as efforts to cool an overheating economy. Second, any delay in identifying neutral rates involves the risk of falling behind the curve, which could necessitate more costly, larger rate hikes in the future to keep inflation expectations under control.

BOJ upgrades core inflation outlook, downgrades potential GDP estimate

We note that the BOJ upgraded its near-term inflation outlook in its quarterly “Outlook for the Economy and Prices” released in January. The central bank upgraded its median core inflation outlook for fiscal 2025 to 2.1% year-on-year from 1.9%, the forecast it had made in October. This upgrade was mostly due to elevation in input prices, which, according to Ueda, was more than “on track”. Meanwhile, the rest of the economy showed signs more in line with stably achieving the BOJ's 2% inflation target, a level around which both headline and core inflation have fluctuated for almost three years.

Another notable, though less apparent, shift in the BOJ's outlook was its modest downgrade to its estimate of potential GDP growth. This, according to Ueda's subsequent comments, was due mostly to the economy's inability to fully meet recovering demand for domestic goods and services given the labour supply shortage, even with the pick-up in capital investments. That said, the downgrade was not entirely negative. Firstly, this is because it means that the bar edged lower for the economy to deliver above-potential growth near-term. Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, the BOJ expects technological advancements, including the implementation of labour-saving investments currently under way, may lift Japan's potential growth. This is an important point for domestic firms, households and foreign trade partners to consider.

Trade uncertainty persists but recent developments show reduced imminent risk

When asked about the uncertainty in overseas economies and markets that prompted the BOJ to pause in December 2024, one of the key risks that Ueda cited was US trade policy and the potential for trade tariffs. This source of uncertainty has clearly not disappeared. However, less aggressively pro-tariff rhetoric from the US President at Davos 2025 with regard to China gave the impression that Washington may be engaging in strategic behaviour. There is still the possibility that the US will take the view that across-the-board trade tariffs may hurt the US consumer and businesses more than intended as we point out in our insight published on 16 January.

On this point, we see the BOJ's perspective of reduced—though certainly existent—risks of large shocks from US trade policy as rational. This is because, in terms of its trade relationship with Japan, the US has much more than its bilateral headline deficit to consider. Its shared long-term strategic interests with Japan, including Japanese investment in the US, are significant. At over JPY 100 trillion at the end of 2023, Japanese investment in the US made the country the top source of foreign direct investment into the US .

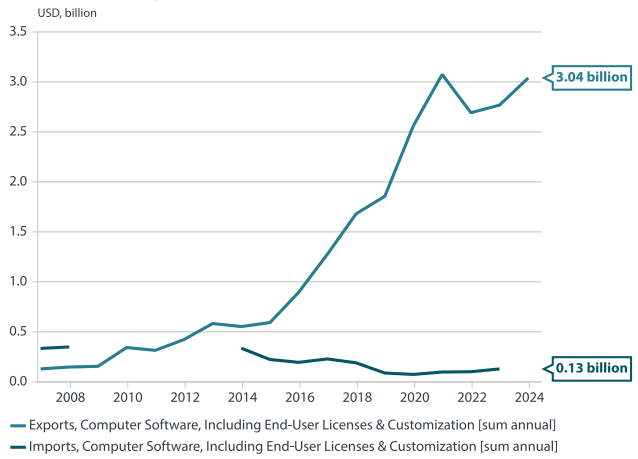

Moreover, in bilateral trade, Japan plays a pivotal role in the US technology industry, a sector in which the US has made massive investments but has not yet fully realized their potential. Currently, the US technology industry is home to the country's largest capitalised listed companies. Japan's net purchases of US computer software, otherwise known as Japan's “digital deficit”, show the benefits the US receives from Japan's adoption of its flagship technologies. On an annualised basis, Japan's digital deficit with the US totals almost USD 3 billion (see Chart 3) and has every reason to continue to expand.

Chart 3: Japan's digital deficit with the US (annualised)

Source: Nikko AM, CAO, BEA, BOJ, COMTRADE

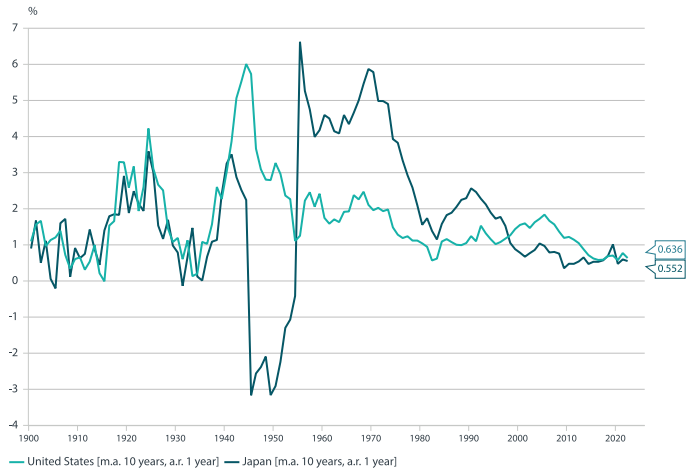

As we noted above, Japan's potential growth has shown a slight decline, primarily due to its labour supply shortages. Japanese companies continue to raise wages to attract and retain scarce labour and invest in labour-saving technologies to ensure they can meet recovering demand. As the BOJ mentions, such investments may, over time, raise potential GDP, provided they are successful in introducing productivity-boosting efficiencies. This implies the need for continuous investment and adoption of labour-saving technologies. As we see in Chart 4, Japan's total factor productivity growth (on a 10-year moving average basis) did trough prior to 2010, but it has remained in modestly positive territory, with growth below 1%.

Chart 4: Total factor productivity has bottomed in Japan; what about the US?

Source: Nikko AM, Long-Term Productivity Database

As we see, however, Japan is not alone in showing total factor productivity (TFP) growth below 1%. By similar measures, US TFP growth peaked in the wake of the early 2000s tech boom, and it has been on a downtrend ever since, even despite the innovations pioneered by Silicon Valley technology giants. It is evident that the productivity-enhancing potential of the sizable capital investments made in Silicon Valley and beyond have not yet fostered widespread gains in productivity in the US economy. This is not to say they never will. However, there could be obstacles for such gains being realised, including the structure of the US labour market. Jobs in the US are pro-cyclical and US labour force participants may fear permanent job losses should AI replace human labour, therefore making them reluctant adopters of automation technology.

In contrast, as we mention above, the demographics and labour supply shortages in Japan, as it recovers from deflationary “lost decades”, make the adoption of labour-saving technologies imperative. With employees much scarcer in Japan compared to the US and the labour structure being less likely to lead to job cuts even in a downturn, there are fewer obstacles to the adoption of labour-saving technologies.

It may be said that Japan is not only the top investor in the US, but also a potential top customer for US-born AI and other software technologies. As a result, it would be prudent for the US to tread carefully with this strategic partner and consumer of its technologies, the potential of which the broader US economy has yet to fully realise.