There is much uncertainty about future US policy, particularly regarding tariff measures that the US may impose on its trading partners. Rhetoric from the incoming US administration appears particularly directed at China, which is a trade partner to Japan and many other economies, large and small. Although the speed and extent to which tariffs will be implemented continue to keep markets guessing, it is helpful at this moment to examine the effects of tariff measures historically. Understanding how these measures and subsequent responses from trade partners have impacted the US economy may give us insight into the potential course of future actions of both the US and its trade counterparts.

Why trade tariffs?

In collaboration with officials such as the US Trade Representative, tariffs are a relatively easy measure for the US president to implement by using Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974. This can be done more quickly than gaining Congressional approval for other types of stimulus measures, especially considering that the US debt-to-GDP is nearing 120%. The optics of tariffs may also appear consistent with exceptionalist rhetoric such as "America First" as a seemingly quick-fix solution to protect US jobs and therefore household real incomes. However, the historical track record of major tariff measures fails to keep up with such intentions.

The Tariff Act of 1930 fell short, in part due to the Great Depression

The US Tariff Act of 1930 raised average US tariffs on dutiable imports by 6% to increase surpluses for US businesses and farmers. Unfortunately, the measure was introduced at the start of the Great Depression, which was responsible for a large part of the subsequent economic slump. Numerous US trade partners retaliated against the tariffs at the time, leading to an overall decrease in US exports of 28%. Specifically, among countries that retaliated with their own tariffs, there was a decrease of up to 32%, according to Mitchener et al (2021) 1 . Indirect consequences of the trade war included the formation of competitive trade blocs among non-US nations, which further affected trade beyond the US. Moreover, tariffs were largely unsuccessful in protecting US jobs. US unemployment rose from 8% in 1930 to above 25% in 1932-1933 and did not return to pre-Depression levels until the Second World War.

US firms, consumers bore the cost in the more recent "America First" trade war

In 2018, the US once again enacted tariffs on its trade partners, particularly China, with the presumed aim of increasing the competitiveness of domestic producers and creating new US jobs. The US imposed tariffs of 10-50% on approximately US dollar (USD) 283 billion worth of imports. Trade partners retaliated by imposing tariffs averaging 16% on around US 121 billon of US exports. According to Amiti et al (2019), the costs associated with these US tariffs were borne almost entirely by US firms and consumers, including USD 3 billion per month in added tax costs plus an additional USD 1.4 billion per month in deadweight efficiency losses. The average cost of manufacturing also rose 1%, according to the same study 2 .

Another study by Fajgelbaum et al (2019) estimated losses to US firms and households (consumers of imports) at around USD 51 billion or 0.27% of GDP 3 . Another unintended consequence of the tariffs was their failure, on aggregate, to create new US jobs. According to Autor et al (2024), the trade war neither increased nor decreased US employment in newly protected sectors. They also found that retaliatory tariffs clearly had a negative impact on employment in agriculture, which were only partially mitigated by agricultural subsidies 4 .

One area in which tariffs did, as intended, cause foreign exporters to lower pre-tariff export prices in the US was in the steel industry. These costs were shouldered by US trade partners such as the EU, South Korea and Japan (Amiti et al, 2020). Yet overseas competitors maintained an edge in global steel production. As such, the tariffs failed to offer much support to the industry, which only grew 2% when overall real US growth was 3%. Therefore the tariffs were largely unsuccessful in creating additional jobs for US steel workers. 5

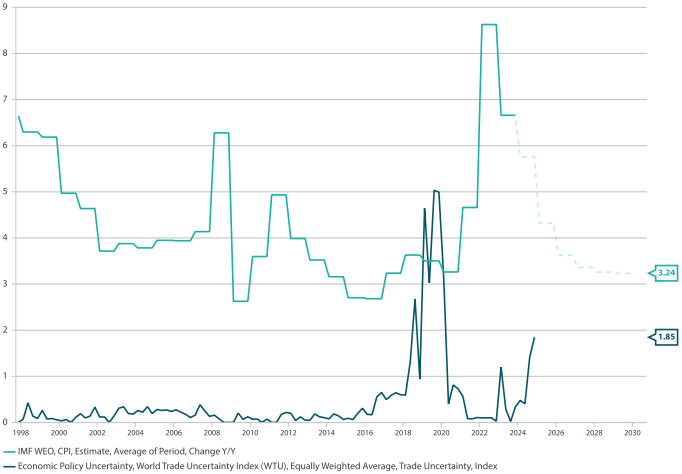

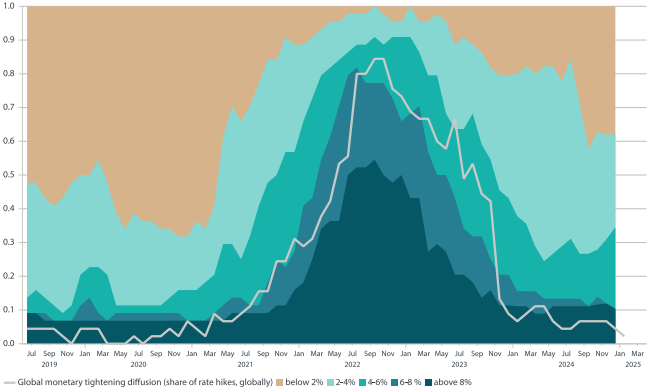

The same study by Amiti et al also cautions against relying on contemporaneous growth or income indicators to measure the trade barriers' full impact. It found that consumers only felt the inflationary impact of the 2018 "America First" trade tariffs after a delay of over one year. The lag in the relationship between world trade uncertainty and global inflation is illustrated below in Chart 1. Indeed, it appears as though the "last mile" of global inflation has been tough to overcome, with many countries stuck in the 2-4% inflation range, even after bringing down price rises from levels of 6-8% or above (see Chart 2). These studies give us valuable insight into the historical impact and effectiveness of US trade barriers, which appear to have hurt US consumers and firms more than originally intended.

Chart 1: Lag between world trade uncertainty and global inflation

Source: Nikko AM, Economic Policy Uncertainty, IMF

Chart 2: "Last mile" of inflation has been tough for many countries to overcome

Global inflation breadth

global core inflation breadth, i.e., share of economies based on different core inflation ranges

Source: Nikko AM, various central banks

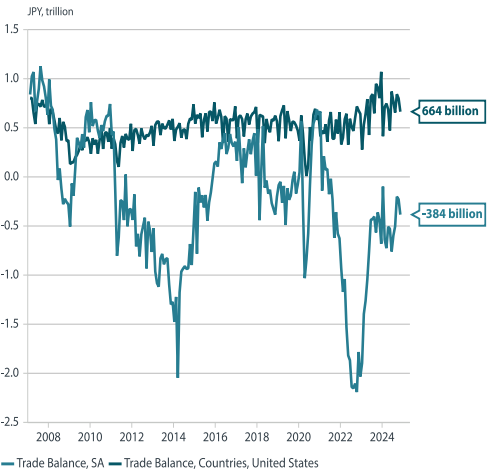

Both direct and indirect impact on Japan

Should the US enact across-the-board tariffs targeting a broad swath of trade partners, Japan would undoubtedly feel the impact. Japanese trade has tended to fluctuate between surplus and deficit ever since the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami, whereupon Japan's nuclear reactors were shut down and the country became increasingly reliant on increased imports of overseas fuel. However, Japan's net monthly bilateral trade surplus with the US often exceeds any net monthly aggregate trade deficit with other trading partners. This implies that any significant disruption to Japan's bilateral surplus with the US could push the balance more frequently into deficits.

Chart 3: Japan's foreign trade (JPY)

Source: Nikko AM, Ministry of Finance (MOF)

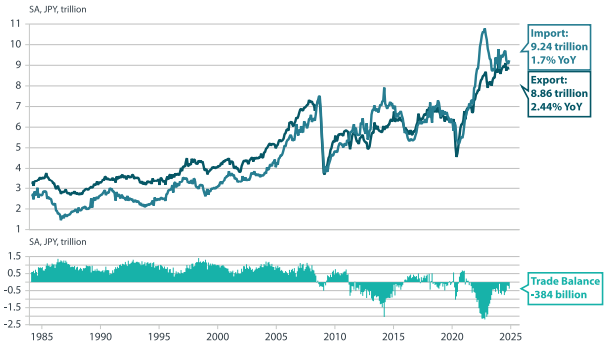

Chart 4: Import value surge contributed to trade deficits

Source: MOF, Macrobond

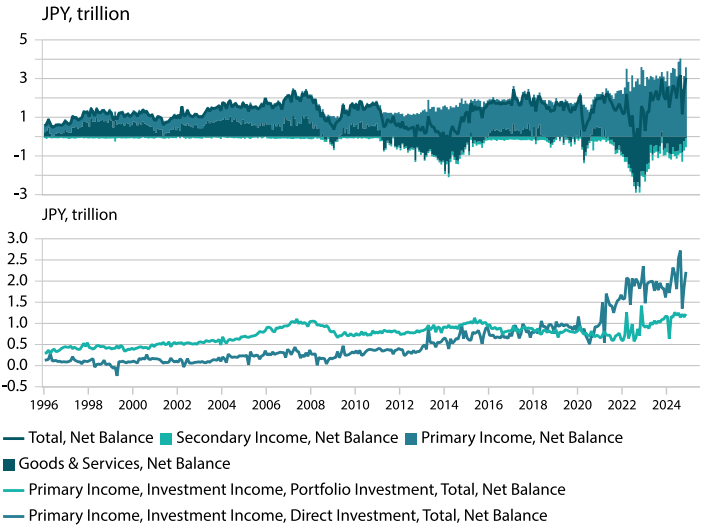

While trade is significant for Japan's balance of payments, investment plays an even more crucial role. As we see in Chart 5, Japan's net trade balance has been dwarfed in recent years by investment income. This includes both direct investment income (e.g. returns on investments in overseas facilities by domestic corporates) and portfolio investment income (e.g. returns on overseas securities investments). Importantly for not only Japan but also the US, the anticipated return on these investments determines the reinvestment or repatriation of this investment income.

Chart 5: Japan's current account (seasonally adjusted, JPY)

Source: Nikko AM, BOJ

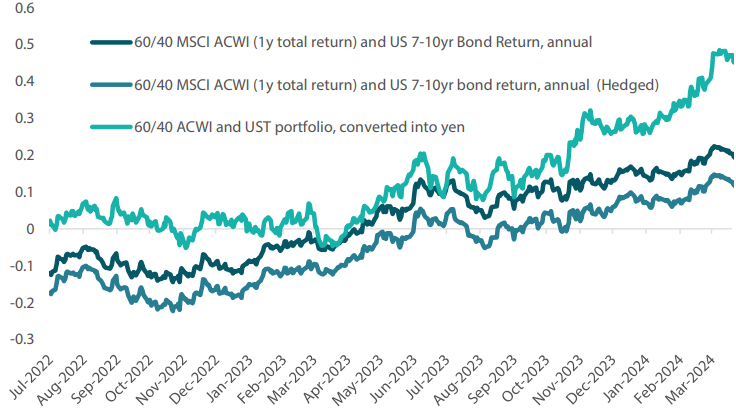

Even as yen weakness has contributed to higher import costs to Japanese consumers and importing firms, it has led to substantial returns for portfolio investors, particularly over the past two years. As shown in Chart 6, a 60/40 portfolio (60% in MSCI ACWI and 40% in 7-10 year US Treasuries) would have offered handsome returns in dollar terms, or even when hedged back into yen with the one-year swap. However, the returns would have been especially rewarding if the dollars were unhedged and simply reflected at spot prices, resulting in on-year gains of almost 50% as at the end of the fiscal year to March 2024. If the US intends to regain export competitiveness, potentially by encouraging a weaker dollar, this should be an incentive for Japanese investors to secure at least some of these windfall gains.

Chart 6: "60/40" portfolio of 60% in MSCI ACWI and 40% in 7 to 10-year US Treasuries

Source: Nikko AM, based on data deemed reliable

How can policy insulate Japan against the impact of US tariff barriers?

Japan does not appear to be the main target of US tariffs. However, Japan's domestic economy is in a crucial transition period, and it continues gradually to recover non-deflationary norms after 30 years of stagnancy. During the transition, any substantial damage to US real growth could prove potentially disruptive, either directly via the trade account or indirectly through the income account. That said, Japan has options to protect itself against both direct and indirect impacts, consisting mostly of policy options. We outline six such options below:

1. Nuclear restarts may prove key to bolstering net exports by reducing reliance on fuel imports

As we mentioned earlier, the 2011 Fukushima disaster and the subsequent idling of nuclear reactors had a significant impact on Japan's external trade balance. One way to protect Japan against diminishing surpluses is therefore to restart nuclear reactors. In fact, reduction of reliance on fuel imports could make a bigger difference on net trade than the direct risk posed by US tariffs. In 2024, the Institute of Energy Economics, Japan (IEEJ) estimated that bringing one additional nuclear plant online could reduce fuel import spending by 0.1% and raise energy self-sufficiency by 0.8%. Bringing additional reactors online may help offset the impact of trade barriers and insulate against unexpected dollar strength.

2. Gradual withdrawal of monetary accommodation

The Bank of Japan (BOJ) has pledged to remain "behind the curve" in terms of withdrawing stimulus and normalising monetary policy to keep inflation around its 2% target. For this reason, the BOJ's gradual but persistent approach to policy normalisation appears rational. To stay on its gradual rate hike path, the BOJ requires continued real wage gains and ongoing increases in financial participation. These factors can help build a domestic demand buffer.

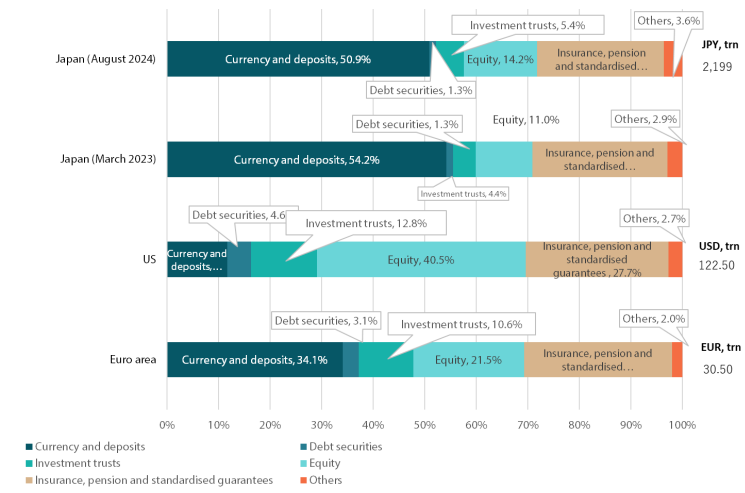

3. Savings-to-investment to build a buffer

The stock market volatility that re-emerged in mid-2024, coupled with doubts over the ongoing US economic expansion, is unlikely to be a temporary phenomenon. Intensifying swings in Japanese indices were not only due to the prevalence of technology-related firms in the Nikkei Stock Average but are also influenced by foreign investor dominance of trading volumes. Foreign investors have leveraged the "carry trade", benefiting simultaneously from stock rallies and ever-cheaper yen funding.

Slowly but surely though, foreign investor predominance of shareholdings is slowly waning as Japanese investors take advantage of tax incentives to move cash savings into financial markets (via the new version of the NISA tax-free investment scheme). The gradual increase of buy-and-hold investments does not prevent valuation declines in volatile conditions, which are dominated by traders rather than investors. That said, domestic investors certainly can benefit from buying on dips amid volatile trading. Chart 7 shows the shift in household savings to investments that has already taken place between 2023 and 2024, after the new NISA took effect. If policy initiatives and improving fundamentals continue to encourage long-term investments in domestic assets (using foreign investment as a portfolio diversifier rather than core investment), Japan may achieve a wider buffer against swings in not only US demand but second-round effects such as foreign investor sentiment on demand for Japanese exports.

Chart 7: A shift in Japanese household savings has been taking place

Source: BOJ

4. Japanese investors can lock in some of their cheap yen windfall

Japanese investors, including pension funds, insurance firms and regional banks, have benefitted to varying degrees from the weak yen. Those who have benefited the most have an important choice to make, which is whether to lock in at least part of their investment income windfall. As we have pointed out above, now may be the time to reallocate or repatriate a proportion of the weak-yen windfall from overseas assets, especially those vulnerable to inflation (such as bonds) to domestic assets (in particular, equities). Such moves would both contribute to and benefit from structural reflation.

5. Governance gains: keep the good news coming

Japanese equity valuations have benefited not only from a return to positive nominal GDP growth, but also from improved disclosures to investors and better returns on risk. We highlighted in Japan's pivotal improvement in risk premium that healthy corporate earnings, improving shareholder payouts and reasonable valuations all played a role in making Japan's equity risk premium competitive again with its US counterpart. It is important both for government and exchange officials to maintain a focus on corporate governance. At the same time, firms need to continue disclosing, raising shareholder payouts, unwinding cross-shareholdings and maintaining other policies that are likely to enhance the returns and therefore attractiveness of domestic equities. This can continue to attract inflows from domestic investors.

6. Making consumption great(er) again

The BOJ can declare victory on achieving its "virtuous circle" of growth once domestic consumption responds to higher real wages backed by expectations that such real income gains can become permanent. This would mean that consumption is playing a more significant role in surpassing potential growth, which the BOJ estimates to be around 0.6%. Getting consumers to incorporate expectations of steady real income growth not only involves higher wages but also controlling inflation, to which yen weakness has contributed. Modest fiscal adjustments by the government —such as raising the primary taxable income bracket—may be helpful without undermining Japan's longer-term commitment to achieving primary balance. For an independent BOJ, this will require walking the fine line between maintaining accommodative conditions and keeping inflation expectations contained.

1 Kris James Mitchener & Kevin Hjortshøj O'Rourke & Kirsten Wandschneider, 2022 "The Smoot-Hawley Trade War," The Economic Journal, vol 132(647), pages 2500-2533

2 Mary Amiti , Stephen J. Redding , and David Weinstein , 2019 "The Impact of the 2018 Trade War on U.S. Prices and Welfare", NBER Working Paper 25672

3 Pablo D. Fajgelbaum , Pinelopi K. Goldberg , Patrick J. Kennedy , and Amit K. Khandelwal , 2019 "The Return to Protectionism" (NBER Working Paper 25638 )

4 David Autor, Anne Beck, David Dorn & Gordon H. Hanson, 2024 "Help for the Heartland? The Employment and Electoral Effects of the Trump Tariffs in the United States" (NBER Working Paper 32082)

5 Mary Amiti & Stephen J. Redding & David E. Weinstein, 2020 " Who's Paying for the US Tariffs? A Longer-Term Perspective ," AEA Papers and Proceedings, vol 110, pages 541-546.