Key Takeaways

- As the green bond market diversifies, Sustainability-Linked Bonds (SLBs) – which are linked to an issuer’s broader sustainability performance – have garnered significant investor attention and scrutiny.

- While the concept is compelling, concerns have arisen that their sustainable targets are sometimes easy to beat and therefore easy to game.

- Structural improvements for SLBs should help make it a more attractive sustainable investment class within the ESG universe.

The green bond market has witnessed significant evolution and diversification. In 2008 the World Bank issued the first labelled Green Bond, pioneering a new approach to financing projects with environmental benefits, such as renewable energy or energy efficiency initiatives. In 2010, at Nikko AM, we formed a partnership with the World Bank to launch our first Green Bond Fund, which focused exclusively on investing in World Bank Green Bonds.

The market has continued to evolve with new types of bonds emerging to address broader social, environmental and sustainability issues. Social Bonds have been introduced to finance projects aiming for a positive social impact, such as affordable housing, education, or healthcare. The International Capital Market Association (ICMA) has also provided guidance on climate transition finance, focusing on instruments for companies looking to evolve from “brown” to “greener”. We have also seen the development of Sustainability Bonds which encompasses both Green and Social Bonds. However, it was the Sustainability-Linked Bonds (SLBs) – which are linked to an issuer’s broader sustainability performance and were a departure from their more popular “Use of Proceeds” siblings – that have garnered most market attention (and scrutiny).

For sustainable fixed income investors, the widely accepted minimum standard for investing in a bond has been set by ICMA principles. These principles define the criteria for Green Bonds, Social Bonds, Sustainability Bonds, Sustainability-Linked Bonds and Climate Transition Finance, and serve as guidelines for issuers to determine the purpose and structure of an ESG bond issuance. However, for most investors, compliance with the ICMA principles, which ideally should be verified by an independent consultant, are just the starting point for whether a bond will be considered for inclusion into an investment portfolio. Further research is always required, including a credit-quality assessment and in-depth scrutiny of a corporation’s sustainability strategy.

Sustainability-Linked Bonds: Innovatively Designed Yet Vulnerable to Gaming

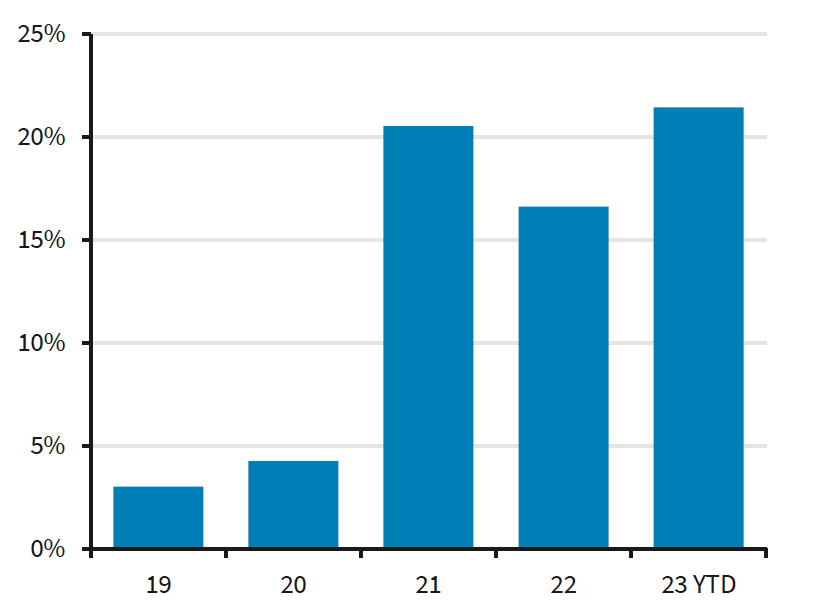

SLBs are the bond type within the group of ICMA principal bonds that has garnered the most investor debate in recent months. The concept behind SLBs is compelling, as issuers define sustainable targets for their business and agree to accept a coupon step-up as a penalty if the targets are not met. SLBs have made up approximately 20% of ‘ESG’ bond issuance volume since 2021 (see Figure 1). They differ from Green, Social, and Sustainability Bonds in that the proceeds are not earmarked for specific sustainable projects but rather for general corporate purposes, opening up the market for hard-to-abate sectors and other companies that would otherwise find issuing green or social bonds difficult. The pre-defined sustainable targets are implemented to ensure that companies are actively working toward a more sustainable future.

Figure 1: SLB issuance as a percentage of total ESG bond issuance

Source: Bloomberg, Dealogic, Barclays Research, Nikko AM (May 2023) Note: excludes local currency debt

The concept of accepting penalties when sustainable targets are not met is a recent innovation. However, SLBs have come under scrutiny as investors have found that the sustainable targets defined by the issuers were quite often easy to beat and therefore easy to game. Commerzbank1 pointed out in a recent research paper that SLB issuers tend to have higher greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (Scope 1 and 2) compared with the average GHG emissions of Stoxx 600 members. Furthermore, the reduction targets of SLB issuers were less aggressive than the Stoxx 600 average. Other questions about SLBs concern the timing of the test dates for their sustainable targets and the lack of an independent target verification mechanism. Often, the test date occurs closer to the maturity date, leaving only one or two years to collect the coupon step-ups. Some issuers even have the optionality to call the bonds after the penalty is triggered, further shortening the collection period. As an example, Enbridge, a US midstream energy company, launched an SLB in March with a maturity date of March 2033, but the first test is only scheduled for September 2031, with an option for a 3-month par call thereafter. Another critical consideration is the low penalty payments. Commerzbank calculated in its research that the average maximum annualised penalty is just below 15 basis points (bps).

1SLBs at the crossroads, Stephan Kippe, CFA, Commerzbank

Any reference to a particular security is purely for illustrative purpose only and does not constitute a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any security. Nor should it be relied upon as financial advice in any way.

Easy-to-beat goals, low penalties and no independent verification mechanism have led to a slowdown in the acceptance of SLBs in the market. Investors to date have been reluctant to include them in their EU SFDR Article 9 funds given the market interpretation around Use of Proceeds and Do No Significant Harm (DNSH). This reluctance is also reflected in bond pricing, while Green Bonds trade at a premium to Brown Bonds, SLBs do not, and they are even sometimes cheaper than Brown Bonds.

Building a Stronger Foundation: Structural Improvements for SLBs to Drive Demand

SLBs require further structural improvements to become an attractive sustainable investment class within the ESG universe. The Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI), a non-profit organisation, summarised in a recent publication what it takes for SLBs to increase in credibility and to see higher demand from sustainable investors. Firstly, an SLB with an environmental angle is only as powerful as the entity’s underlying transition plan and the ambition of associated performance targets. Secondly, SLB targets should include all material scopes of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (scope 1-3). Thirdly, it’s advisable to avoid GHG economic intensity targets and select absolute GHG emissions targets or intensity targets with a unit of production as the denominator. Lastly, it’s important to avoid weak features in the bond structure, for example a call before the first KPI test or step-ups only kicking in at the maturity date.

The most recent issuance from TDC, a Danish telecom operator, offered an SLB structure that has the potential for wider acceptance as it aligns closely with CBI recommendations. Firstly, TDC has implemented an ambitious climate strategy that aims to reach net zero across its entire value chain (Scope 1, 2 and 3) by 2030. These targets received external independent validation from SBTi (Science Based Targets initiative) and Sustainalytics, which provided a Second-Party Opinion and classified the targets as “Highly Ambitious” – its highest rating. The reduction goals outlined in the bond indenture appear ambitious and are in line with TDC’s disclosed 2030 net-zero pathway, which aims for a reduction of its Scope 1 and 2 Greenhouse Gas emission (GHG) by 80% and Scope 3 by 35% by 2027. If the company fails to reach these targets, the bonds will be outstanding for another 3 years and allow investors the opportunity to harvest the step-up. The only criticism to note is the step-up amount is only 12.5bps, which could have been higher. Nevertheless, this structure demonstrates more meaningful progress compared with other issuances witnessed in recent months.

There is still a lot of work ahead for investors to engage with issuers to better incorporate the CBI and ICMA recommendations and to increase the appeal of SLBs for sustainable investors. Barclays highlighted in a recent publication that not all SLB issuers have fully embraced the ICMA SLB standards. Nonetheless, it’s a worthwhile effort to develop alternative bond structures for the “use of proceeds” category. The appeal of SLBs is clearly the fact that they require the issuer, as a whole, to move toward a more sustainable future and be willing to accept penalty payments if targets are not met. However, the definition of those targets needs more work before SLBs will make their way into sustainable investment portfolios more fully.

Finally, it is important to emphasise that SLBs are not only important for corporate credit issuers, but even more so for sovereign issuers. A single sustainable investment project is often not critical to an entire country. What is more relevant, is how the country treats its natural resources and the wider environment in general. Last year Uruguay and Chile issued SLBs targeting nationally determined emission cuts – an exciting development that showcases the potential for SLBs.

Any reference to a particular security is purely for illustrative purpose only and does not constitute a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any security. Nor should it be relied upon as financial advice in any way.

For any questions in regards to this report, please contact:

Nikko AM team in Europe

Email: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.