Introduction

Japan may not be known for quick, sweeping reforms. However, developments in the country’s corporate governance over the last 10 years suggest that once changes are set in motion, they can have a deep and lasting impact, raising the value of its companies and creating investment opportunities along the way. We assess how companies are adapting to changes in the corporate governance landscape, explain how a shift in the overall ownership of Japanese equities paved the way to reform and highlight the potential catalysts for further investment opportunities ahead.Signs of change: Japan Inc. beginning to disclose management plans

Dusting off simple business matrix from the early 1970s

Many readers may be familiar with the growth share matrix, also known as the product portfolio matrix (PPM), popularised in the early 1970s by Boston Consulting Group (BCG) founder Bruce Henderson. For the uninitiated, the matrix is a table consisting of four quadrants, each of which is represented by symbols that display various degrees of profitability: star, question mark, cash cow and dog (Exhibit 1). The PPM helps companies prioritise their businesses by enabling executives to decide where to concentrate their resources to create value or reduce losses. The matrix has been utilised by a significant number of the largest US companies and remains a key tenet of corporate strategy to this day.

Exhibit 1: Product portfolio matrix

- Question marks: products with high market growth but a low market share

- Stars: products with high market growth and high market share

- Dogs: products with low market growth and a low market share

- Cash cows: products with low market growth but a high market share

Source: BCG. PPM diagram compiled by Nikko AM.

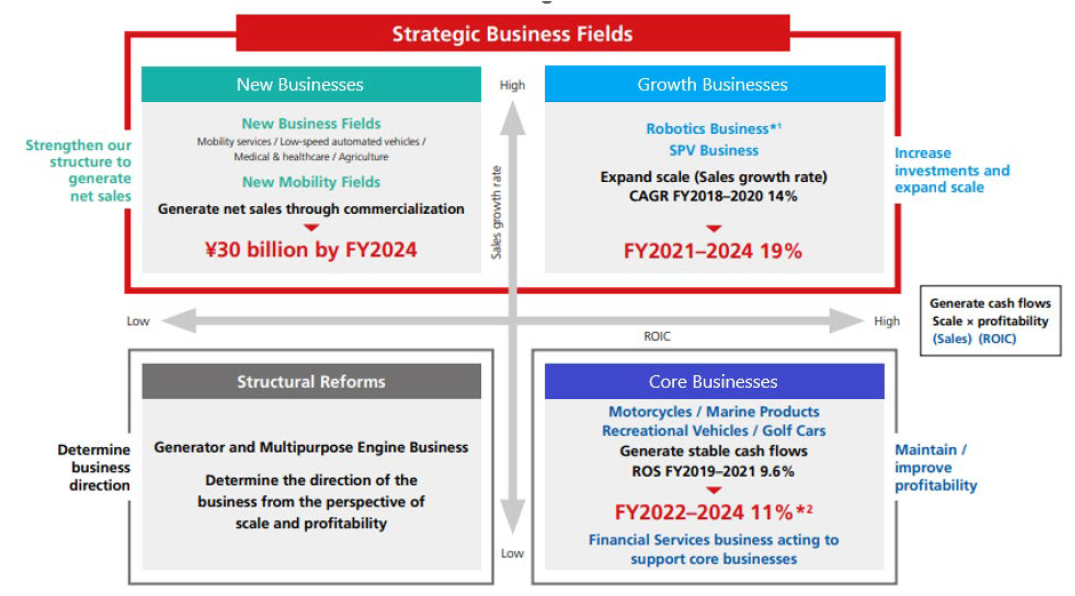

Now, let us fast forward more than 50 years since BCG’s Bruce Henderson first popularised the PPM among Fortune 500 companies. Exhibit 2 shows Yamaha Motor Company’s business portfolio plan released at the end of 2021 as part of its 2022-2024 medium-term management plan—an example of a company’s business plan based on the PPM. By using a four-quadrant table, a company is logically able to explain what it plans to do to improve profitability.

Exhibit 2: Yamaha Motor’s medium term management plan (2022-2024)

Source: Yamaha Motor

In Yamaha Motor’s example, the company stated that “We intend to identify the businesses that require structural reforms from a perspective of scale and profitability over the period of the new Medium Term Management Plan”. Yamaha Motor’s decision to openly disclose which businesses it would target for structural reforms left a strong impression on both its employees and outside investors. After disclosing the above medium term management plan, Yamaha Motor in 2023 sold its power products business which produces multi-purpose engines, generators and snow blowers; it also recently announced plans to pull out of the snowmobile and swimming pool businesses. What Yamaha Motor is doing is a case of a company generating cash with its core businesses (higher ROIC, lower sales growth) and transferring the cash to its new and growth businesses. This is a classic example of a company taking a logical step to diversified business management—an approach that many Japanese companies are just beginning to embrace.

Japan lays down a marker by introducing the Corporate Governance Code in 2015

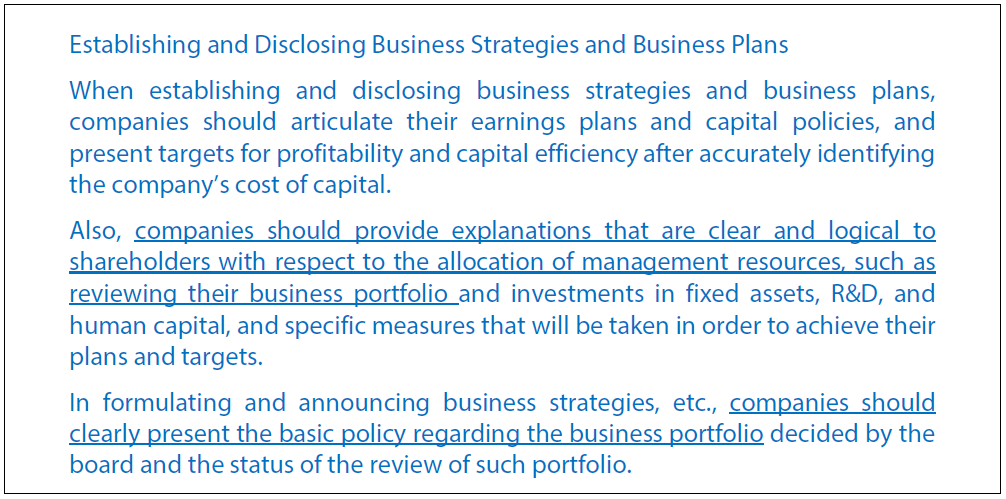

Why did Japanese companies begin adopting a logical business portfolio management approach? We believe the answer lies in the introduction of the Tokyo Stock Exchange’s (TSE’s) Corporate Governance (CG) Code in 2015. The CG code, revised in 2018 and 2021, set down guidelines for listed companies to pursue elements such as timeliness, transparency and fairness in their decision-making while emphasising the needs of shareholders. The TSE takes a “comply or explain” approach in which listed companies can either comply with the CG code’s guidelines or are asked to provide a full explanation if they opt not to comply. As Exhibit 3 shows, the TSE places particular emphasis on companies disclosing business strategies and plans.

Exhibit 3: Except from the TSE’s Corporate Governance Code revised in 2021

Source: Principle 5.2 of TSE’s Corporate Governance Code revised in 2021

The long and winding road to corporate governance reform

Why it took so long

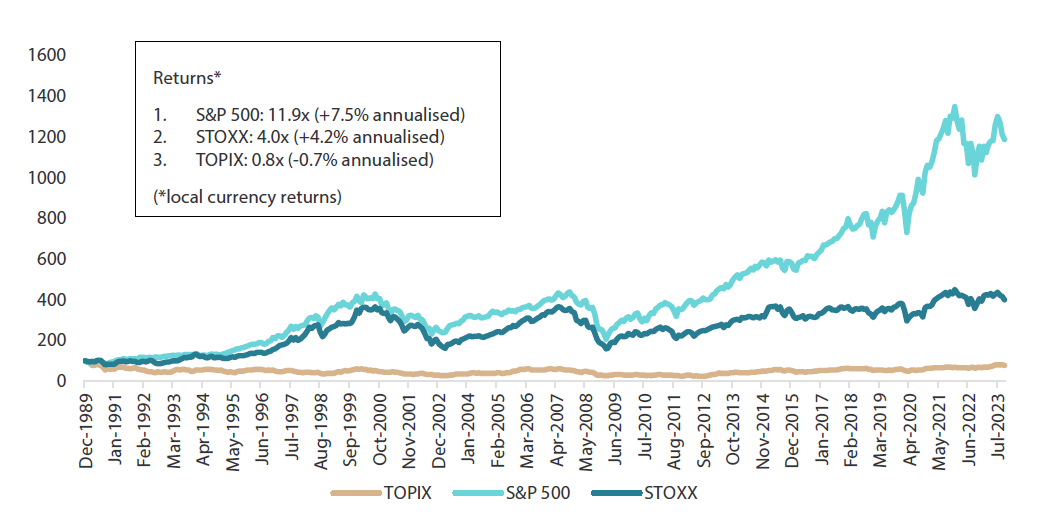

Foreign observers may wonder why it took so long for Japanese companies to begin adopting PPM-inspired business principles popularised half a century ago. We believe that long-established tendencies of companies to neglect minority shareholders and not always prioritise maximising shareholder returns hindered Japanese firms from taking a more logical approach to business management. Chart 1 of the historical return rankings of the world’s major stock indices shows the consequences of Japanese firms neglecting minority shareholders, which in turn made the country’s equities unattractive from a very long-term perspective. The chart is rebased to 100 in December 1989, the year Japan’s TOPIX reached a record high. The TOPIX has only scraped out a return of 0.8 times since 1989, but in contrast the S&P 500 has produced one of nearly 12 times while that of European stocks (denoted by EURO STOXX) has quadrupled during the same time period.

Chart 1: Japan’s TOPIX has lagged its US and European counterparts over the past 34 years

Source: Bloomberg as at 31 October 2023

Brief history of corporate governance in Japan

Age of bank governance: 1950s–early 1990s

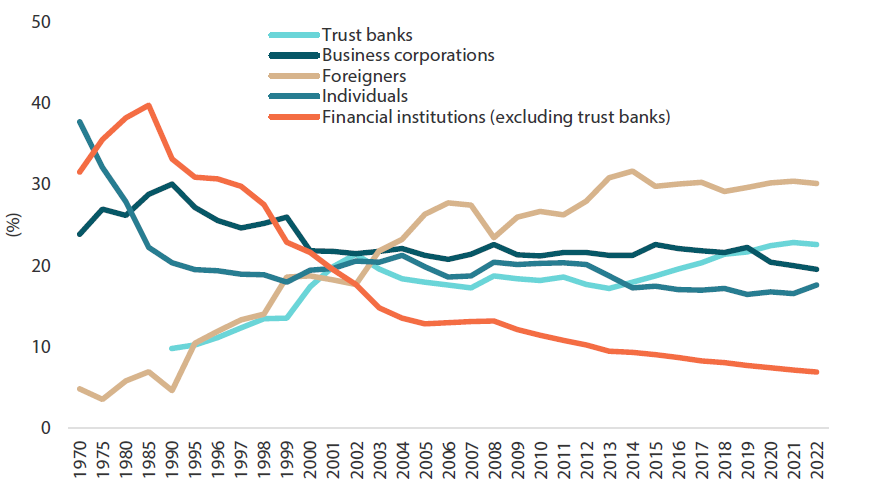

Japan’s history of minority shareholder neglect can be tracked back to the 1950s, when the country was beginning to rebuild itself from the ravages of the Second World War. Large banks played a big role in corporate governance during this period as they not only provided businesses with loans but exerted influence by transferring their own employees to important positions such as accounting director etc at the firms to which they lent. In these arrangements banks formed inner circles within firms with themselves at the core. These arrangements prioritised corporate growth, which favoured the firms’ management, their clients, suppliers and the banks, but they also resulted in inefficiency and left minority shareholders in the periphery. Banks’ influence on corporations, however, waned after the bursting of Japan’s asset bubble at the start of the 1990s. In turn, foreign investors began filling the void left by banks that had to focus on addressing the mountains of bad loans they found themselves straddled with. Foreign investors now boast the biggest presence in Japanese equities, holding approximately 30% of the market (Chart 2).

Chart 2: Foreign investors have steadily increased their market presence

Source: TSE as at July 2023

The age of institutional investor governance: early 1990s–present

As foreign investors and activists began to exercise more influence, corporate practices which had plagued Japan for decades came under increased scrutiny. These included “parent-subsidiary” listings (when a parent company and its subsidiary are listed on the same exchange, often creating conflicts of interest), cross-shareholdings, use of takeover defence measures and the above-mentioned neglect of minority shareholders. Taking such criticism to heart, the administration under then-Prime Minister Shinzo Abe declared in 2013 that corporate governance reform would be one of the main agendas of its flagship reform drive (“Abenomics”) intended to revive the economy after two decades of stagnation. Japan followed through with the introduction of the Stewardship Code in 2014 and the Corporate Governance Code in 2015.

The Stewardship Code lays down guidelines for institutional investors to adhere to and continues to shape Japan’s governance landscape. As of September 2023, 329 asset-managing institutions, including 82 pension funds, were signatories of the Stewardship Code. From a governance perspective the behaviour of Japanese asset managers has changed significantly since the introduction of the code. Most of Japan’s major asset management firms are subsidiaries of large financial groups and the code has helped alter the previously cosy relationship between these two groups. For example, asset managers rarely opposed management decisions made by investee companies through the exercise of voting rights if their parent institutions had business ties with the investee companies. Being signatories of the code, however, has meant that an asset manager is obliged to improve the corporate value of investee companies by exercising their voting rights regardless of the relationship an investee company may enjoy with their parent institution. Under the code, asset managers need to have clear voting policy guidelines and are required to disclose their voting activity. These changes have altered the conservative approach asset managers had towards the exercise of voting rights. Asset owners who entrust their funds to asset managers often are also signatories of the code. This has meant that asset managers, under pressure themselves from asset owners, are in turn increasingly engaging with investee companies.

The opportunities ahead

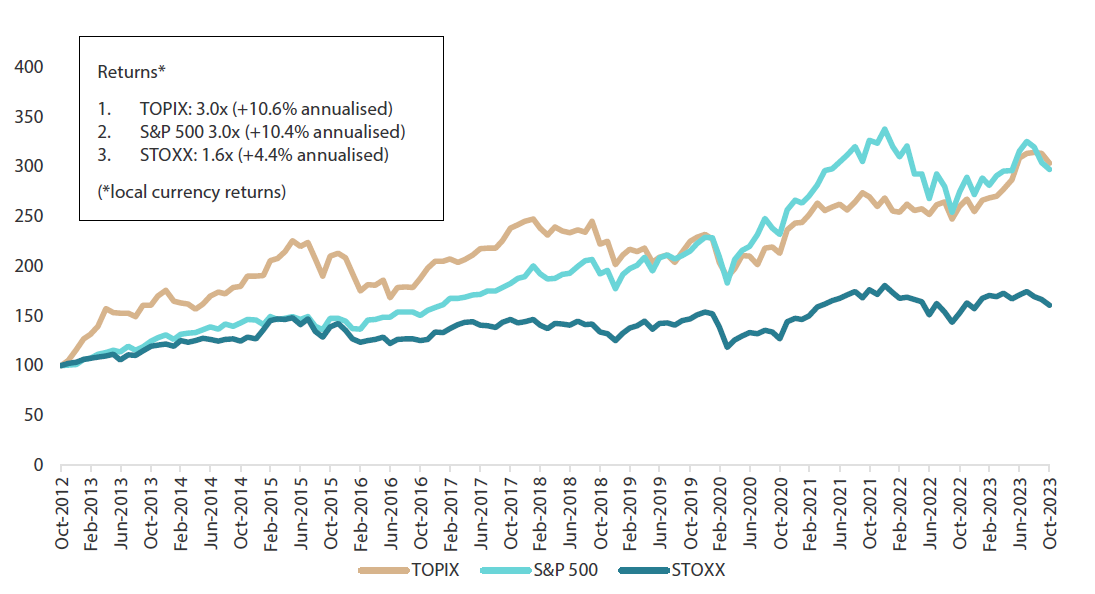

We began our presentation on a sombre note by showing the underperformance of Japanese equities over a period of three decades in Chart 1. However, when we shorten the timeline to the last 11 years, Japan’s TOPIX has actually performed roughly on par with the S&P 500 (Chart 3). If we were able to remove the marquee GAFA names from the S&P 500, it wouldn’t be difficult to imagine the TOPIX outperforming its US counterpart; it has certainly done better than STOXX.

Chart 3: TOPIX has gone toe to toe with the S&P 500 over the past decade

(Rebased to 100 in October 2012, just prior to the start of Abenomics.)

Source: Bloomberg as at 31 October 2023

We believe that the corporate governance reform introduced at the start of the Abenomics era has played a significant role in buoying Japanese equities over the past decade. This may only be the first of several chapters of fundamental change impacting the market. We see at least two more phases ahead: corporate restructuring and deregulation.

Corporate restructuring

In a recent interview with a major Japanese financial broadsheet, an official with a large US asset manager suggested that there were many similarities between the current Japanese market and that of the US in the 1970s and 1980s. He highlighted the presence of many conglomerates in the US during that period which began to see the advantages of shedding non-core businesses as corporate governance became an important market agenda. The restructuring of US conglomerates was seen to have created numerous investment opportunities. The dissolution of the conglomerates in the 1980s coincided with a period in which PPM-inspired corporate strategy had become all the rage. Decades later, Japan Inc. could follow in the footsteps of its US peers as firms embrace corporate governance in earnest. Additionally, the Action Guideline for Corporate Takeovers, compiled by the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) in August of 2023, aims to encourage business restructuring and grow the Japanese economy by stimulating corporate takeovers. NIDEC and Dai-ichi Life Holdings have already implemented takeover bids in line with this guideline, and the effect looks promising. We see investment opportunities being created as a result of restructuring among firms and even whole market sectors.

Deregulation could lead to “buy and engage” from “buy and hold”

Japan’s Financial Services Agency (FSA) is currently considering amending the “large shareholding reporting rule” that investors are subject to. Under current regulations, investors are required to submit complex and detailed reports when their holdings of a company’s outstanding shares exceed 5% and thereafter have to repeat the process each time their holdings increase by 1%. Investors can now be exempt from filing the very time-consuming reports if they agree not to engage in subjects grouped under “the act of material proposal”. The list, however, includes subjects that can determine share values, such as listings and de-listings, election or dismissal of company CEOs, changes to corporate boards, demergers, acquisitions and stock swaps. The current rules, established before the introduction of the Stewardship Code, are seen as obstacles to effective engagements between investors and firms, prompting the FSA to consider amending the regulations to encourage large shareholders to engage with investee companies without excessive administrative burdens. Under the FSA’s recently published draft amendments to the rules, engagements normally carried out by institutional investors are interpreted as not constituting “the acts of material proposal”. Accordingly, we believe that the amendments will further stimulate engagements between investors and investee companies and open up new investment opportunities. We could see investors transition from “buy and hold” to “buy and engage” in the near future.

Summary

- Corporate Japan is beginning to adopt business practices based on PPM popularised half a century ago. The concept of maximising shareholder returns has taken root in Japan after a long delay.

- Minority shareholders were left out in the cold during the post-war bank governance era that lasted until the early 1990s. However, in a new governance in era in which foreign investors, activists and domestic institutional investors have taken a leading role, Japanese companies are placing a higher priority on shareholders.

- The corporate governance reforms which began in 2013 are still underway. In an encouraging sign, Japanese policymakers like the FSA, TSE and METI appear determined to carry on with the reforms despite several changes in government. Japan’s TOPIX has performed on par with the S&P 500 during this period, reflecting the effectiveness of the reforms. As with the US many decades ago, the Japanese market could witness significant corporate restructurings. This, together with prospective deregulation, could open up new investment opportunities.

Any reference to a particular security is purely for illustrative purpose only and does not constitute a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any security. Nor should it be relied upon as financial advice in any way.