For days, there were long snaking queues of frustrated-looking customers desperately waiting to withdraw their money from a bank fighting for survival. As the frantic bank run entered the second week, the embattled financial institution—drained of its coffers—was forced to seek assistance from the country’s financial authorities, which eventually seized full control of its operations before placing it under a recapitalisation and restructuring program.

As recent as it may sound, the above narratives on a bank run are not depicting the plight of recently collapsed US banks. No, we are not talking about Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) nor Signature Bank, but Indonesia’s Bank Central Asia (BCA) back in 1998.

Fast forward to today, BCA is now the largest and amongst the most well-run banking franchises in Asia with a whopping Common Equity Tier 1 ratio of 25.9%...yes, that is right, roughly one quarter. Given the ongoing turmoil in the developed world’s banking systems, we thought it would be apt to pen our thoughts about risk of contagion in the Asian banking sector and what has been changing for regional banks in recent years.

Any parallels between Western and Asian banks?

Let us first address whether there are any parallels between what has occurred in the banking arena of the US and Switzerland and the Asian bank universe. To be sure, one could write an entire research piece on what went wrong at the respective institutions. But in our view, the recent blow-ups of SVB, Signature Bank and California’s Silvergate Bank as well as the Swiss government-brokered buyout of troubled Credit Suisse by rival UBS all seemed to boil down to two things—the pressure exerted by higher interest rates and ultimately poor risk management and oversight.

While interest rates continue to rise globally, we would note that rate hikes across most Asian countries have been of a smaller scale (240 basis points [bps] on an equally weighted average) as compared to the US, whose central bank has raised rates by a total of 475 bps since March 2022 in a bid to tame rising inflation.

Second, interest rates in the region, despite moving higher over the past year, are only back to their 10-year averages and still well below the levels during the pre-Global Financial Crisis era. In addition, there has been a notable step up by Asian central banks such as those of Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan in terms of their prudent regulation and supervision to limit the negative impact on credit costs and banking system stability.

In terms of the growing concerns about the over-reliance on Additional Tier 1 (AT1) capital and contingent convertible (CoCo) bonds, we would point out that these capital debt instruments are few and far between in Asia, where most banks significantly exceed the regulatory targets on core equity capital. (AT1 and CoCo bonds, which generally pay a higher rate of interest to bondholders, are designed to absorb losses when the capital of an issuing financial institution drops below the mandated regulatory level.)

Prudent regulation and supervision by regional financial authorities

While security exposure as a proportion of total assets is much lower across most banks in Asia, several Taiwanese financial institutions (including insurers) had already raised capital during the second half of 2022 after incurring interest rate-related revaluation losses on their security books. Exposures are more elevated in Indian state banks and Chinese regional banks. But in our view neither are likely to be inflicted with deposit runs given both their diversified and sticky retail base; in addition, rates are lower in China. We would also note that in terms of regulation, liquidity coverage ratios and net stable funding ratios are applied to both large banks and regional banks in the countries where the regulations are most advanced.

Asian financial regulators learnt the hard way with the Asian financial crisis (or the “IMF Crisis” in local parlance) still fresh in the memory of most bankers and regulators in the region. Since then, in our opinion central banks in Asia have been amongst the most prudent and disciplined financial regulators in the world. Take Singapore for instance; the total debt servicing ratios (or debt indicators that help financial institutions assess their borrowers’ total outstanding debt obligations before loans are granted), which were introduced in mid-2013, were further tightened just before the Federal Reserve’s current monetary policy tightening cycle.

Another recent example is Taiwan’s judicious issuance of digital banking licenses. In the 1990s, when 19 new licenses1 were given out to private consumer-facing banks in general, a devastating credit card crisis ensued in Taiwan and today, only one of those banks remains an independent standalone entity, with the rest either bankrupt or sold and acquired as distressed entities. Learning from its mistakes, Taiwan issued only three digital banking licenses back in 2019 with very stringent requirements on what these entities are allowed to do. As such, a US dollar 42 billion-a-day digital bank run scenario (as experienced by SVB on 9 March 2023) in Taiwan is highly unlikely to unfold, in our view.

1 Takatoshi Ito and Anne O. Krueger, “The Reform of the Business Service Sector: The Case of Taiwanese Financial System”

Areas of positive fundamental change in Asian banking systems

Where does digital banking make most sense? We would contend it to be in cash-based, underbanked and geographically sparse countries such as Indonesia, the Philippines and India—all of which are underpenetrated in terms of financial services. Our recent discussions with a bank in Indonesia confirmed that the cost to acquire a customer using the mobile app service was only one-tenth the cost of acquiring that same customer in a branch. Gone are the days of rapid branch expansion to reach out to more and more people in rural areas. To be sure, there will be significant cost efficiency benefits to come for regional financial institutions that are embracing digital banking, leading to a sustained improvement in their profitability.

In India, positive fundamental change is afoot. Two pivotal reforms have dramatically improved the functioning and outlook for Indian banks in recent years. The country’s Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code effectively shortens bankruptcy proceedings from one of the most drawn-out legal processes in the world of around four to five years towards a more commonly accepted period of two years. Secondly, the Real Estate Regulation Act dramatically cleans up the industry towards a more sustainable growth path. In recent years, the successes of India’s Aadhar identification verification system and Unified Payments Interface have also made banking and payments in the country significantly more seamless in what was previously a largely cash-based economy. These, together with “Made in India” and the Production Linked Incentive Scheme, could be supportive drivers of credit demand.

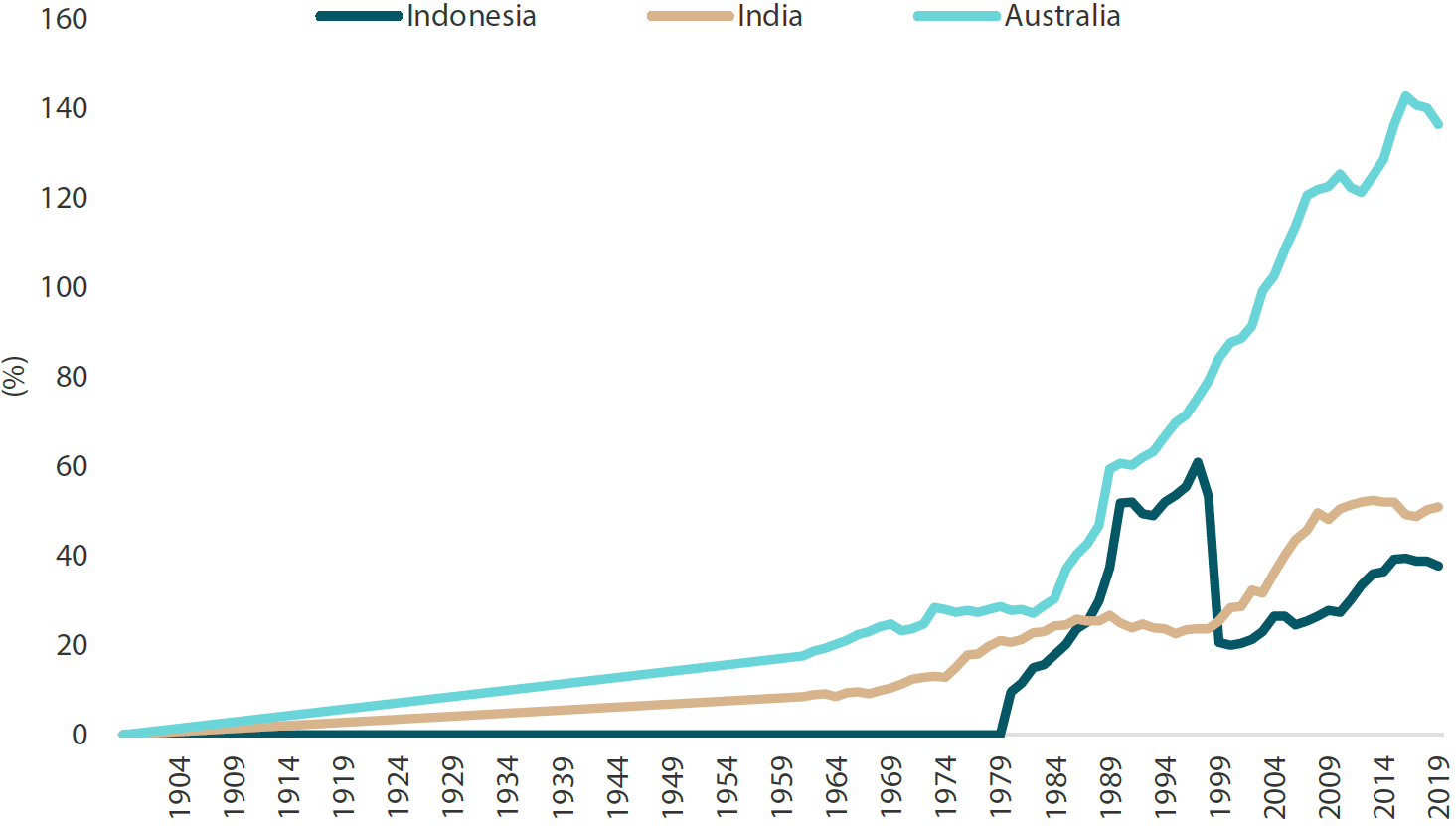

Both India and Indonesia have not seen any significant growth in credit as a percentage of their nominal GDP in over 14 and seven years, respectively (see Chart 1). This is despite both countries being relatively underpenetrated economies in terms of financial services. This may, however, not be a bad thing in a rising interest rate environment, where credit risk generally increases.

As we have noted from a capital and funding perspective, both India and Indonesia have considerable balance sheets, which are ready to be deployed into growth opportunities, be it in new manufacturing industries in technology (such as Apple’s increased production in India) or electronic vehicle and downstream material processing in Indonesia. (For more information, please see our Net zero made in Asia article and the Outlook for Asian equities investment guide.)

Chart 1: Domestic private credit to nominal GDP (%) of Indonesia, India and Australia

Source: The World Bank

Source: The World Bank

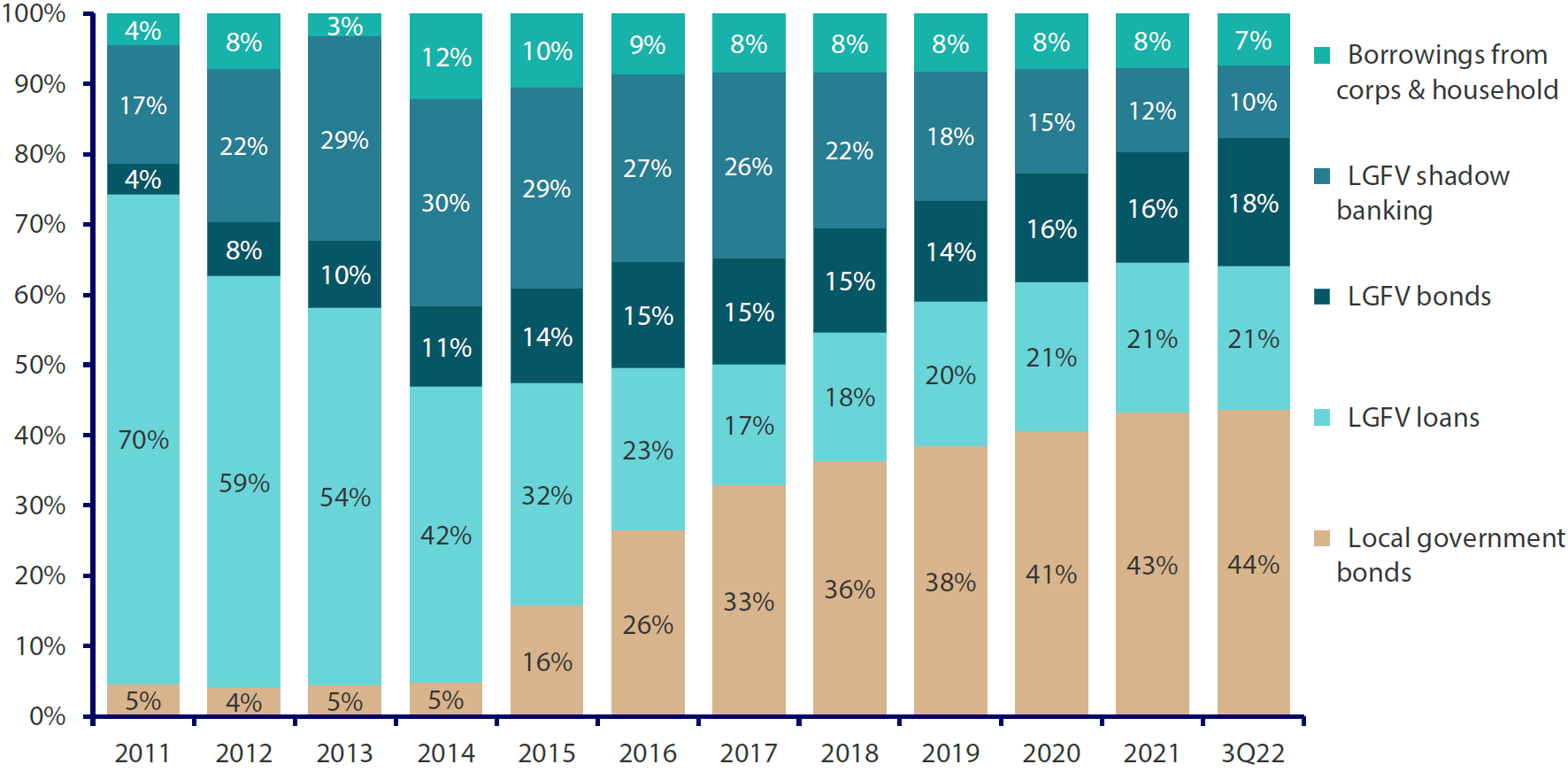

Even in China, where debt levels remain at high levels, the financial authorities have been working to address any potential systemic risks in the country’s financial system, namely in the areas of shadow banking, local government financing vehicles (LGFVs) and the property sector (see Chart 2 for the breakdown of China’s local government debt by channels). This has been a pre-cursor to positive reform. The long-awaited private pension reform programme could be a huge opportunity for insurers, asset managers and banks in time in a country where the bulk of household savings are still in deposits and property assets.

Chart 2: Breakdown of China’s local government debt by channels

Source: CLSA, PBOC, CBIRC, Chinabond.com.cn

Source: CLSA, PBOC, CBIRC, Chinabond.com.cn

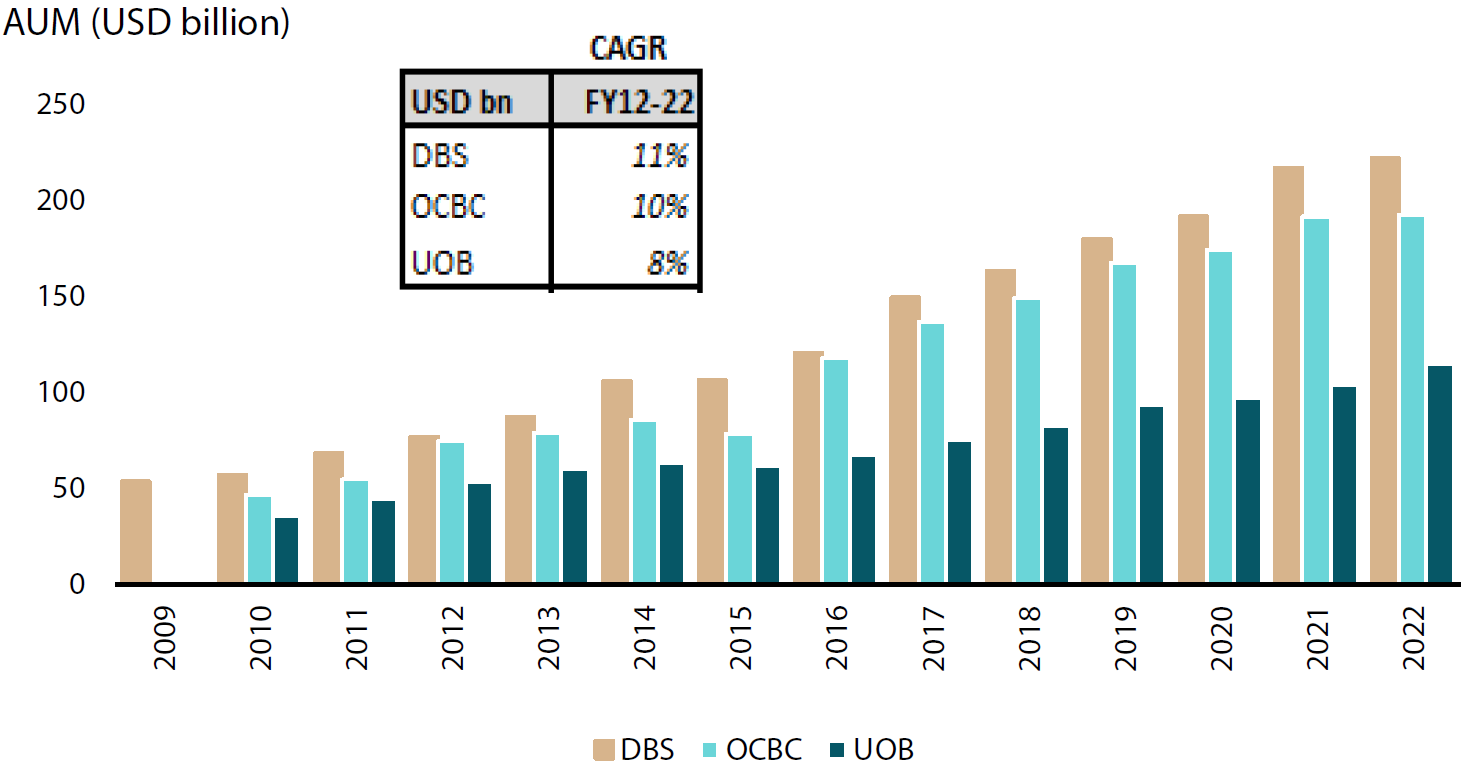

One other important area a little closer to home and one that the Credit Suisse saga is unlikely to undermine is Singapore’s thriving private banking and wealth management sector, which remains a key strategic area of focus for local banks (namely DBS, United Overseas Bank [UOB] and Oversea-Chinese Banking Corporation [OCBC]) in the city state. Singapore stands out more and more in terms of regulatory prudence and good management, especially for being the “not China option” versus rivalling financial centre Hong Kong. As we see it, the Singapore regulators are also actively incorporating and promoting new investment structures (such as the Variable Capital Company Act) to bring more business to the city state. All in all, Singapore banks have experienced strong asset under management (AUM) growth over the past several years (see Chart 3).

Chart 3: Singapore banks ‘strong AUM growth

Source: Company reports, UBS

Source: Company reports, UBS

Risks and opportunities in Asia’s banking sector

We do not, however, look at Asia through rose-tinted spectacles. There are some pockets of risk within the region. Although the likelihood of deposit runs on the majority of Asian banks remain low, that cannot be said for all recently formed digital banks, where the build-up of fast money deposits is likely to witness some volatility. Thankfully in most countries in Asia, these entities have not grown to be sizable parts of the overall financial system. Nonetheless, we would view with caution standalone players that do not have strong parentage or are not part of a broader company ecosystem (such as in e-commerce).

In addition, the stock of debt is high in countries like China, South Korea and Thailand, while credit growth as a percentage of GDP has risen materially in Indochina, which is now being worked through in the case of Vietnam. These are areas we should remain vigilant on, but as China re-opens, Asia as a whole should see some welcome growth impulse.

On the whole, positive change has been more abundant in recent years. Once we get through this current US-led rate tightening cycle and rationalisation of those financial institutions that were addicted to zero interest rates (more in the non-bank financials we suspect), the future seems bright for Asian banks, which are now trading at much more attractive valuations.

Reference to individual stocks is for illustration purpose only and does not guarantee their continued inclusion in the strategy’s portfolio, nor constitute a recommendation to buy or sell.