Introduction

Until recently, Japan was lauded as one of the few countries that successfully limited the COVID-19 outbreak. However, more than a year into the pandemic, Japan’s slow vaccine rollout is coming under increased scrutiny with the country lagging far behind its G7 peers in vaccinations. We explain the reasons behind the sluggish rollout, review the prospects for inoculation gathering speed, analyse the potential impact of the summer Olympic games being held at a delicate time for the country and assess the prospects for the economy, political situation and markets post-vaccination.

Japan’s healthcare system: Universal but fragile in crisis

Japan’s still low infection rate less of a comfort in second year of pandemic

Before looking at Japan’s vaccination rollout, it’s worth examining the country’s healthcare system and why the still relatively limited number of infections is less of a comfort with the pandemic in its second year. The main feature of Japan’s healthcare system is that all residents, in theory, are eligible to receive medical care through a universal healthcare plan. This has resulted in easy access to healthcare: most residents would not think twice before visiting the doctor, even at the slightest hint of a cold. Providing Japan’s large population with habitual access to healthcare is a vast number of small-scale private clinics and hospitals that can be found in any neighbourhood. These institutions are ill-equipped to deal with a pandemic. In contrast, large, public hospitals with the staff and equipment necessary to handle an outbreak are few and far between. This means that the entire healthcare system, despite the large number of registered medical personnel and hospital beds, is quickly stretched to the limit during national emergencies such as a pandemic. With such a fragile healthcare system, the only option available to the government is to limit economic activity in the hopes of controlling the movement of people and thus the number of infections, even if the number of severely ill COVID-19 patients is relatively low. Speeding up the vaccine rollout is therefore of paramount importance both from a medical and economic view.

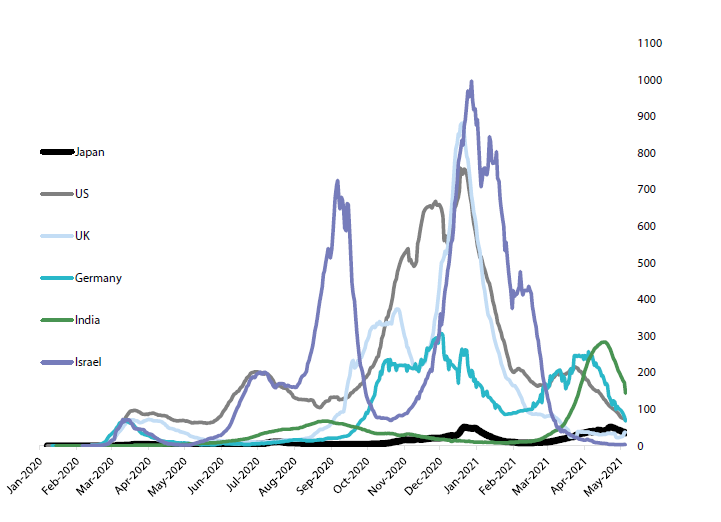

Chart 1: New COVID-19 cases per million people

Source: Our World in Data, as at 27 May 2021

Source: Our World in Data, as at 27 May 2021

Why Japan’s vaccination efforts have lagged

We can identify two main reasons for Japan’s slow rollout. First, Japan has so far been unable to develop its own vaccine and is therefore reliant on imports; in other words, it essentially needs to wait until vaccine-producing countries are first done inoculating their own populations. Japan is home to some pharmaceutical companies with the potential ability to develop COVID-19 vaccines. However, the government, unlike its peers in countries such as the US, failed to swiftly provide Japanese pharmaceutical companies with the incentives for speedy vaccine development. Second, Japan has a particularly onerous approval process for pharmaceuticals—developed because of numerous drug disasters in the past—which considerably slows the development and import of vaccines. For example, Japan, where only the Pfizer coronavirus vaccine had been approved, did not give the green light to the Moderna and AstraZeneca vaccines until 20 May as the authorities conducted trials in Japan to evaluate their efficacy and safety. Furthermore, stringent regulations mean that, until recently, only nurses and doctors were able to administer vaccines.

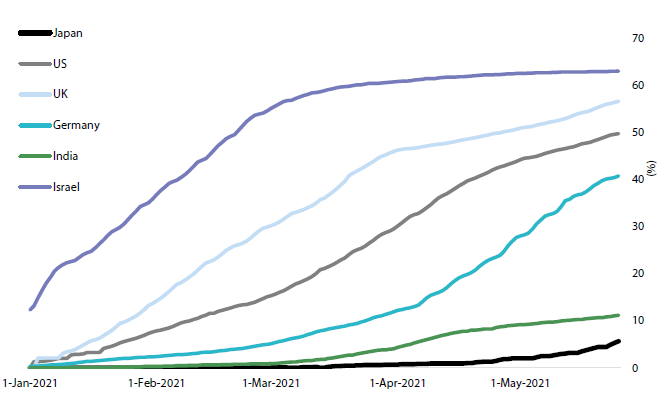

Chart 2: Percentage of population receiving at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine

Source: Our World in Data, as at 27 May 2021

Source: Our World in Data, as at 27 May 2021

Vaccinating the elderly key to re-opening the economy

Japan aims to inoculate those 65 years or older by end-July

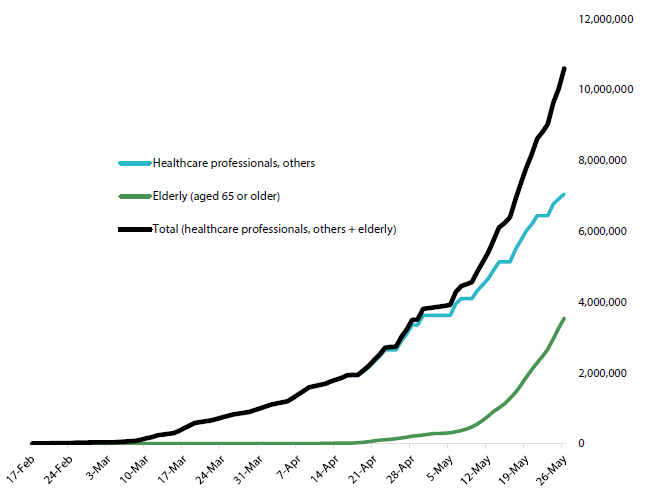

The government’s plan is to prioritise the inoculation of those aged 65 or older, representing 36 million people, or 30%, of the population of 126 million. The inoculation of the elderly began on 12 April and the government aims to vaccinate the entire age group, roughly equal in size to the population of Canada, by the end of July. While inoculations have gathered pace after a slow start, about a million shots still need to be administered daily for everyone in the age group to be fully vaccinated by the end of July. Despite the formidable task, 93% of local governments plan to vaccinate elderly within their constituencies by the target date, according to the media. Following a sluggish start, vaccination in Japan is finally gaining momentum (Chart 3). State-run mass vaccination centres were opened in Tokyo and Osaka, Japan’s two largest cities, on 24 May, with the government recruiting the country’s military to operate the venues. Local governments in other areas are also planning to set up their own mass vaccination sites, with baseball stadiums being considered as potential venues. Stringent regulations are also being softened so Japan can deal with a shortage of eligible medical staff. Japan recently allowed dentists to administer COVID-19 vaccines, and, according to local media, the government is considering adding clinical laboratory technicians and paramedics to the list of eligible medical professionals.

Chart 3: Total number of vaccine doses administered in Japan

Source: Office of the Prime Minister and the Cabinet, as at 27 May 2021

Source: Office of the Prime Minister and the Cabinet, as at 27 May 2021

Inoculation of the elderly will significantly alleviate the strains currently placed on Japan’s medical system. For a country such as Japan with a sizable percentage of older citizens, vaccinating a large segment of the population most at risk of severe illness caused by COVID-19 will allow the government to ease economic restrictions even if overall infection rates remain relatively high. Once the elderly are inoculated, the government will not have to wait until a large majority of the population, such as 80%, is vaccinated before easing economic restrictions.

Elections to come into focus once vaccinations gain traction

It will be in the best interests of current Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga to ease economic restrictions as soon as possible, in our view, as that would allow the premier to call a snap election for Japan’s powerful House of Representatives1 (lower house). Suga’s term as president of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), and thus his term as prime minister, expires at the end of September. The best-case scenario for Suga would be for him to dissolve the House of Representatives, quickly call a snap election and lead the LDP to a lower house victory before his term as LDP president runs out. That would put Suga on track to retain his position as party president when the LDP chooses its leader in September. We therefore need to view easing of COVID-19 restrictions and the normalisation of economic activity through the perspective of Japan’s politics, as reducing the number of severely ill patients and freeing up hospital beds through vaccinations could shore up support for Suga, currently seeing a steady decline in public approval ratings, and pave the way for an early snap election.

1The four-year term for members of the lower house expires on 22 October 2021, requiring the appointment of new-term members through a general election.

Dilemma for Japan as public support for the Olympics wanes

The summer Olympics and Paralympics to be hosted by Tokyo in July are also likely to impact political developments. If the vaccinations proceed as planned, the inoculation of the elderly should be almost completed by the time the games begin late in July. Regardless of how vaccinations proceed, the Olympics could still create a dilemma for the Suga administration. Many public polls currently show the majority of Japanese residents either opposed to hosting the games or in support of further postponement. If Japan goes ahead with the Olympics, Suga’s already low approval rating could suffer even more—something he surely wants to avoid before the upcoming election. It’s also worth noting that if the government were to do an about-face and cancel its hosting of the Olympics, the impact on the economy and markets would likely be limited. While 90,000 athletes and related personnel are expected to come to Japan for the games, the number of foreign tourists visiting the country at the same time will be virtually zero. Inbound demand created by such a limited number of visitors is bound to be minimal.

Conclusion

Instead of the Olympics, Japan will likely look to domestic demand to kick start its economy once a significant portion of its population is vaccinated. Vaccination and the subsequent normalization of economic activity will help revive sectors that were hit hardest by the pandemic, notably those related to travel (both business and leisure), tourism, lodging and food and beverages. The government backed “GoTo” campaign, which provides travellers and diners with discounts, should help get the economy back in shape by resuscitating these downtrodden sectors, in our view. From a market perspective, the normalization of economic activity means a recovery in shares of companies that were given the value label during the pandemic, such as those linked to railways, airlines and hotels. Only when Japan is back on its feet with the help of measures such as the GoTo campaign can we turn our focus to post-pandemic economic trends such as decarbonization, which appears to have made progress helped by Suga’s initiatives, but still likely faces many uncertainties before Japan can genuinely benefit from it.